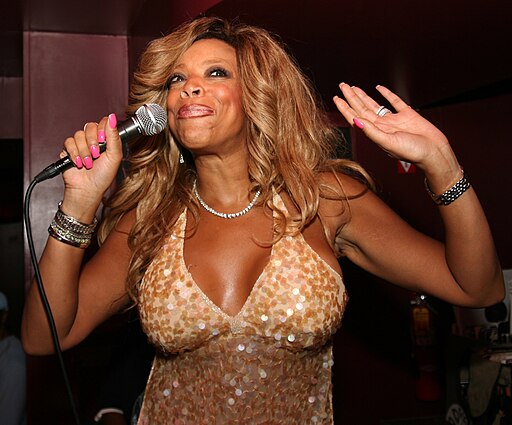

This past week, former talk show host Wendy Williams went public with her primary progressive aphasia and frontotemporal dementia diagnosis, revealing that her doctors confirmed she had the disease last year.

The condition is a rare nervous system syndrome where people can slowly over time lose the ability to speak and write and eventually may no longer be able to understand written or spoken language. It also can lead to problems with memory and changes in personality including lack of concern for others or oneself, poor judgment, or inappropriate social behavior.

In William’s new documentary, “Where is Wendy,” which aired this weekend on Lifetime over two episodes, the disease is front and center for all to see, with Williams struggling at times during interviews to find the right words or slurring as she speaks. At other times, she becomes erratic, shouting profanities like, “I don’t need a F—ing therapist,” when the producer of her documentary asked her if she didn’t like going to a therapist or calling a nail tech stupid after bonding with her just two seconds earlier.

This is in no way a judgment of Williams who I greatly respect and admire for her courage and willingness to show her prognosis for all to see on camera. Another great icon I admire is Bruce Willis, who shares William’s disease and came forward with his diagnosis in 2022. Examples like this, while incredibly hard, are necessary and important for raising awareness about all types of dementia and the struggles that come with it.

Much of what I saw from William’s behavior mirrored my own mother’s experience battling early-onset Alzheimer’s for over 15 years. While the two diseases are entirely different, they do share similarities, including erratic behavior. I distinctly remember my mother, who grew up in religious rural Ireland and rarely ever swore, calling the people she loved fecking egits (which means “F—king idiots in Ireland) a few years into her diagnosis.

What’s sad about situations like this is that unlike Wendy and my mother, who have access to care, millions of dementia patients do not, putting them at great risk (and in some violent situations their loved ones and caregivers). Many are forced to deal with the repercussions of a disease they did not ask for and have no measures in place to properly address it or get the care they need.

According to a 2022 study published in Frontiers in Neurology, barriers to dementia assessment and care include stigma about dementia, poor patient engagement in and access to healthcare, inadequate linguistic and cultural validation, limited dementia-capable workforces, competing healthcare system priorities, and insufficient health financing.

While this burden is especially high in low- and middle-income countries, within the U.S. it is also a burden with big factors being the lack of a universal healthcare system in place and the exorbitant cost of exams. For any case of dementia, imaging exams like MRI and CT are required to keep track of how far these diseases progress. Without insurance, the nationwide cost of an MRI on average is $1,361, according to healthcare e-commerce company MDSave.

Even in William’s case, cost is a concern. In her documentary, she reveals that her bank accounts and assets are frozen in Wells Fargo due to her being “the victim of undue influence and financial exploitation.” As a result, Williams, who was placed under a financial guardianship by the Supreme Court of New York in 2022 after a former financial advisor told the bank that she was of “unsound mind,” says she has no access to her money, which could affect and possibly prevent her from being able to access care in the future.

Additionally, transportation barriers can keep people from making their way to doctors or facilities with the resources they need. We who live in urban and suburban areas often take this for granted, but in rural settings, even ten miles can be an impossible feat because people may lack access to a car or public transport. And even with any form of transport, getting dementia patients to facilities can be challenging, as some are prone to violent outbursts. I remember my mom grabbing the wheel of the car while I was driving one time. You never know what these people are going to do next.

Dementia, regardless of what type it may be, is like an automatic switch that activates and causes the person to react within a split second, with no regard for others or the ability to contemplate their actions and the consequences of them beforehand.

In these situations, many might be inclined to say that such people should be placed in a long-term care facility, but this again brings us back to the number one issue, which is cost. According to a 2019 study out of UC San Francisco, cost was one of the reasons why most seniors with advanced dementia remain at home. Those who did had more chronic conditions, experienced more pain, and were more likely to fall or concerned about falling. In residential facilities, patients had less depression and anxiety, fewer chronic conditions, and less unintentional weight loss, but the average cost for these places was $48,000 a year.

What’s especially concerning is that these are just seniors. There are a growing number of people, including my mother and Wendy Williams, who are being diagnosed with early-onset forms of dementia. While some may be still young and healthy, dementia does eventually take its toll on the body no matter who you are, and for those out there who do not have access to appropriate care, the burden falls on them if they are alone or on their loved ones who may be financially unprepared to handle these situations themselves.

Unfortunately, the solution is not quite clear. Yes, we could go the usual route and blame the government for not doing enough to fund dementia care resources, but that is only partially the issue. Much of the problem is the insurance companies and hospitals and their monopolization of the competition over the past few decades which has allowed them to hike the price of care up astronomically.

Additionally, the insurance companies have created a tangled mess of their in-network and out-of-network providers, making it at times impossible to know which facilities are suitable insurance-wise for patients to get the care they need. This has all but catapulted fears of going to hospital for care due to the financial gravity of the price that comes with such care. Insurers and hospitals are now required to disclose pricing for certain services, but even that is a nightmare to navigate, with many facilities and insurers compiling hard-to-read, 1990s-style computer pages that list each service, one after the other with no periods or commas to distinguish them. And calling these companies is often futile, as many people do not know how to look up the cost of service or say they cannot give an answer until they have seen the patient.

I wish I had the answer. I wish I knew the key actions to take to address these issues head on so the U.S. could do better by its citizens suffering with dementia. But even if I did, I’m sad to say that I doubt much would change, as creating better and affordable access to care for dementia and other patients requires everyone, or at least enough of the majority of people, to be on the same page politically, financially, and business-wise, and share the same social attitude. And that is something I am afraid to say is impossible, at least with the current state of our country…and the world today.

Leave a comment